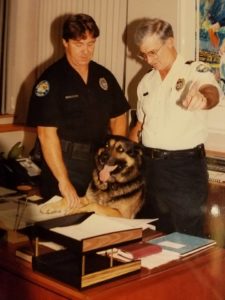

Officer Skip Brown and Chief Rick Overman celebrate Rambo’s retirement. Rambo was a legendary K-9.

The Delray Newspaper broke a story last month that reminded me how much a dedicated police officer can mean to a community and to someone in need lucky enough to bump into the right cop at the right time.

In November of 1995, Officers Skip Brown, Dan Grose and Rosetta Newbold were on patrol when they responded to a call in a drug and crime riddled trailer park. In a rancid trailer that defied description they found two small children, ages 7 and 8, who were dirty, hungry and scared.

The two, a brother and sister, had roaches crawling on their faces and in their hair. When Skip carried the little girl to safety, she clung tightly to his neck. He promised her she would be OK. And he meant it.

Skip is that kind of guy.

I know that from personal experience which is why I cherish him and his wife Cheryl.

Skip took the boy and girl back to the Police Department and comforted them as best he could. The little girl would never forget his kindness.

Eventually state child welfare authorities intervened and the children ended up in foster care. Skip never forgot about the children and frequently wondered where they were and if they were Ok.

The little girl spent years searching for the kind hearted officer. But police officers can be hard to find and there are many Skip Brown’s in this world. (But none like our Skip Brown).

Then recently, she caught a break.

Regular readers of this blog will recall that about a year or so ago, Skip—now happily retired in Alabama— came home to receive a much deserved and long overdue Bronze Star for his heroic service in Vietnam.

He chose Old School Square as the venue to receive his medal and he chose me to pin the star on his chest. It was the biggest honor of my life. We are close friends and Skip has been an older brother to me—which means he can be tough on you but you also know that he’d jump in front of a train to save you from being run over. I would do the same for him.

The publicity around the Bronze Star ceremony prompted a story in an Alabama magazine and that led to a discovery….the little girl…saved in 1995 and now an adult… wrote to the magazine’s editor with a request.

Could she be put in touch with the man who showed her such a big heart all those years ago?

The editor reached out to Skip and a reunion via email and phone ensued. It’s a heartwarming story and our Associate editor Marisa Herman did a remarkable job writing about the saga.

Here’s the link: https://delraynewspaper.com/former-delray-police-officer-reconnects-with-girl-he-rescued-24-years-ago-27572

Please read the story and share it. It’s a heartwarming saga in a world that needs to see more of these kind of stories.

But this column is about my friend and brother Skip.

By all accounts, we are an odd couple. I’m moderate/liberal, he’s conservative. I’m 5’9”, he’s well over 6 feet. I’m a New Yorker, he’s from Ohio. I’m young (wink)…he’s…OK we’ll stop there.

Yet our friendship has always worked.

Which shows you that surface differences really don’t matter. What matters is what’s in your heart and what you really care about. On that measure, we have just about everything in common.

Skip has a heart for people in distress and animals, especially dogs but also birds, cats and just about anything that crawls. I do too.

Skip cares about community. We bonded over our mutual love for Delray and our rock solid commitment to try and make this a better place for everyone, young, old, black, white, east, west you name it.

Skip made a big difference in his 20 years of service. He started as a cop in a vastly different Delray Beach—working the road, serving as a K-9 officer, staffing midnight shifts where gunfire and violent crime happened every night.

We spent many of those nights talking late into the wee hours on my driveway at the end of his shift about Delray, great dogs and life itself.

Over time, like the layers of an onion, he revealed much about himself and his experiences—the heartaches, what combat is like, the stresses of being a police officer and the ability to make an impact in some instances while other times you are just helpless and watch as your heart breaks over some situation—whether it’s an elderly volunteer succumbing to cancer, the loss of my mother, the loss of Skip’s brother, the nastiness of politics and the plight of a little girl and her brother living in a squalid trailer.

When Jerrod Miller was shot, 14 years ago this month, Skip was there as we worked to try and keep our city from falling apart in the wake of tragedy.

These experiences bond you—as brothers. They forge you and make you stronger even though you are never quite the same and the scars accumulate.

We’ve been there for each other through the loss of loved ones, the loss of great dogs (Rambo, Olk, Magnum, Casey), moves, career changes, divorce, illness and all the changes that come with time.

He has always had my back and I love him for that and for always having the backs of everyone in his life.

On the side of most police cruisers in America is the saying “protect and serve.”

For the best officers, the ones who make a real and lasting difference, those words are more than a tagline they are a bedrock philosophy and a way of life.

Even when they retire, the best officers continue to protect and serve—their family, friends and neighborhoods. My friend is one of those special people and I just needed to share that with you.

We attended SUD Talks on Saturday night at the Crest Theater.

We attended SUD Talks on Saturday night at the Crest Theater.